point you do have to say, "How much is this going to cost that you guys are

all conjuring over there in London?" 'Cause right there what you could do is

go outside to the castle and do a dissolve. And I went away and wrote this

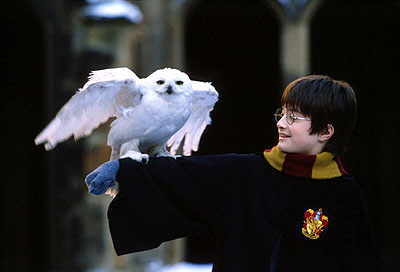

incredibly complicated visual idea, which was that Harry takes the owl out

into the snow and that he flies away and the seasons change, and he comes

back. Now, you're not seeing what I initiallyy wrote because what I

initially wrote evidently came in at something like $750,000, the most

expensive paragraph I've ever written in a script. But what you are seeing

is a pretty close approximation to it. I love that moment because it is

Harry alone; it is that pensive moment, it's that kind of melancholy, and I

think it's oddly moving. You're seeing the bird fly away and things change.

You're right, those moments were really conscious choices on my part. I

always wanted to spike the movie with those kinds of moments because I feel

Harry is a kid who is emerging literally and metaphorically from darkness.

There is a shadow over him, and I felt we always had to express that, that

everything is not just hunky-dory once he gets to Hogwarts. Not just because

of the peril he faces from the outside world, but he has an interior

landscape that is a little dark because of where he comes from. It's

something Jo can express in prose, but visually how do you express Harry's

interior landscape? The moment with the owl was really it for me.

point you do have to say, "How much is this going to cost that you guys are

all conjuring over there in London?" 'Cause right there what you could do is

go outside to the castle and do a dissolve. And I went away and wrote this

incredibly complicated visual idea, which was that Harry takes the owl out

into the snow and that he flies away and the seasons change, and he comes

back. Now, you're not seeing what I initiallyy wrote because what I

initially wrote evidently came in at something like $750,000, the most

expensive paragraph I've ever written in a script. But what you are seeing

is a pretty close approximation to it. I love that moment because it is

Harry alone; it is that pensive moment, it's that kind of melancholy, and I

think it's oddly moving. You're seeing the bird fly away and things change.

You're right, those moments were really conscious choices on my part. I

always wanted to spike the movie with those kinds of moments because I feel

Harry is a kid who is emerging literally and metaphorically from darkness.

There is a shadow over him, and I felt we always had to express that, that

everything is not just hunky-dory once he gets to Hogwarts. Not just because

of the peril he faces from the outside world, but he has an interior

landscape that is a little dark because of where he comes from. It's

something Jo can express in prose, but visually how do you express Harry's

interior landscape? The moment with the owl was really it for me.

Click to visit Top X Snape sites!

Back to Snape's Dungeon | Назад в подземелье проф. Снейпа

Serve Detention (Chit-Chat) | Снейп-чат